BOMRONS OVER BISCAY

Five Navy Liberator Squadrons Knocked Out 14 Subs During Campaign to Sweep U-Boats from Atlantic

IN the gray light of the English winter dawn the ponderous white-bellied Liberators waddled down the runway and lifted slowly into the sky. Out over the

rocky Devonshire coast and the choppy waters of the Channel they streaked south toward the Bay of Biscay, hunting grounds of the enemy's undersea fleet.

Over the Bay the crews suddenly became alert, shaking off the drowsiness induced by their early rising and the constant drone of the four engines. Waist

gunners stared at the faint line of the horizon almost imperceptibly separating the gray of the sky from the gray of the sea. Bow and crown turrets whined

and twisted, their twin .50-caliber guns seeming to search for every dot in the air that would mean a Ju-88 or any change on the surface that might indicate

a U-boat.

This day the search was more intense. One of the big boats had failed to return from the night's patrol. From the northern shores of Spain to the Brittany

coast, shuttling back and forth only 100 or so feet above the choppy waters, they watched for a life raft or a cluster of small yellow patches; a drifting wisp

of smoke or a white-starred wing.

Twelve, fourteen grueling hours later the big planes circled the base and wearily settled down on the flare path. One by one they came to rest on the

hardstands. Only one had news.

Somewhere on the vast Bay the crew had sighted two oil slicks in the patrol area of the night's missing Lib. One patch was small, the other large. On the

official reports the plane and crew were listed as missing in action but that was not their only epitaph. To Coastal Command headquarters went the one phrase

for which they had worked so long and arduously: Probably destroyed enemy submarine.

Such was the perilous job of five Navy patrol bombing squadrons comprising Fleet Air Wing 7, now back in the States. Front-line fighters in the Battle of

the Atlantic, they struck at the very heart of Germany's U-boat campaign, hunting the enemy in his own waters before he could reach Allied convoy lanes with

his destructive torpedoes, and sinking 14 of the undersea raiders.

When Hitler's legions stormed down through the Low Countries and into France in the spring of 1940 they not only wanted to defeat and drive from the

Continent the British and Allied armies but, on Hitler's orders, they wanted to secure for Admiral Karl Doenitz, then chief of Nazi "unterseebooten,"

adequate bases from which to launch a submarine offensive of unprecedented magnitude. When the Nazi armies finally halted they had driven all the way

to the Spanish border on the Atlantic coast of France. It was there, in the Biscay ports of Brest, Lorient, St. Nazaire, La Pallice and Bordeaux,

that the great sub pens with their massive roofs and complex underground repair and supply depots were built and from there that the U-boats sallied

forth on their missions of destruction.

With outmoded Swordfish, Whitleys, Wellingtons and even early Flying Forts, Coastal Command of the RAF opened a blockade while what bombers

|

| Official U. S. Navy photograph |

| NAVY LIBERATOR takes on gas at its base in England as crewmen ready it for a Bay of Biscay sub-hunt. |

-- 18 --

|

| Official U. S. Navy photograph |

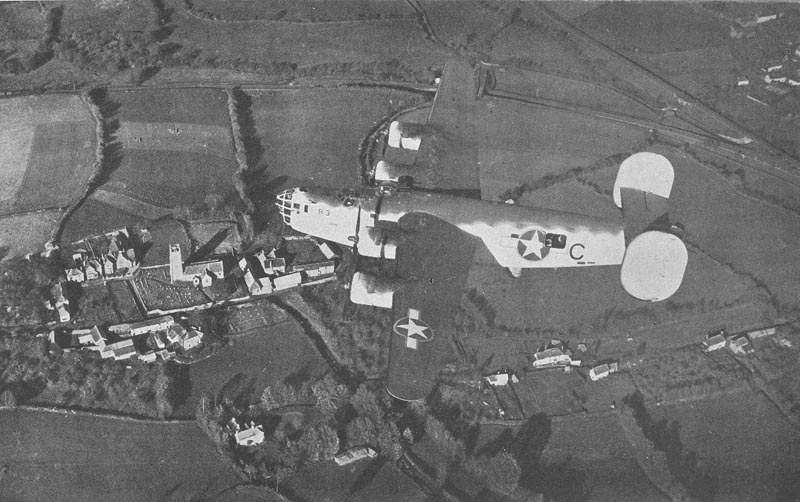

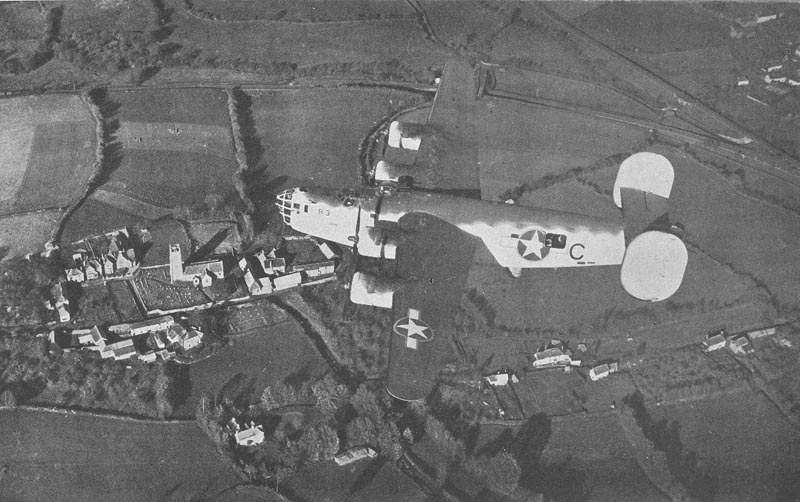

| BACK FROM BISCAY roars the four-engined sub-buster, winging over the checkerboard landscape of rural England. |

were available attacked the bases. Soon after arriving in England in the summer of 1942 America's 8th Air Force contributed squadrons to the battle. Then

three veteran Navy squadrons - 103, 105 and 110 - relieved the Army and joined in the fight.

They knew the task before them as a child knows its alphabet. They had learned it by rote, flying from bases in the South Pacific, Caribbean, North and

South Atlantic. Some of the pilots had piled up 200 missions - 10, 12, 18 hours at a stretch, with the roar of the engines drumming into their memories the

slogan of antisubmarine patrol planes:

"Even without bombs you can keep 'em down."

Their first patrols were similar to the milk runs out of the Stateside ports, monotonous and uneventful except for weather that would ground a seagull. After

a few weeks the men seldom knew where they would land on their return from the Bay. Unpredictable weather made diversion a habit rather than a rarity.

Action came quicker than the flying bluejackets expected. Two planes disappeared over Biscay in the first week of operations. Then Lt. James A. Alexander,

USNR, later killed on a training flight, ran into a formation of six Ju-88s over the Bay. The venomous long-range, twin-engined fighters were roaming the skies

as escorts for outbound subs. Lt. Alexander's gunners shot down one 88 and damaged others and he and his co-pilot were awarded DFCs and Purple Hearts, the first

decorations for naval aviators in the European theater.

Still the Navy airmen had not as yet met the enemy for which they were searching-U-boats. Early one morning four Navy Libs were out over the Bay on routine

patrol. One of them sighted a submarine running on the surface, charging its batteries. In response to an urgent call for assistance the other Libs sped to

the scene followed by other Coastal Command aircraft. The German sub was harried above and below the surface from 0400 until dusk when it was finally destroyed.

A final assessment gave a Czech-manned Liberator 50% of the kill, an RAF Wellington 10% and the remaining 40% to the Navy.

For Navy men accustomed to the best service food in the world, and the smooth efficiency and cleanliness of seaside bases, the United Kingdom proved tough

on the ground. Although their arrival had been expected no provisions had been made for operating the base Navy style. An RAF regiment-the base defense force

dished out Spam and brussels sprouts. Military police, ordnance and supply companies were U. S. Army detachments. Other RAF units were in charge of maintenance

of runways, hangars, roads and living sites. Only aloft did the men feel at home.

There was enough business in the air to keep them occupied. Along with their Biscay patrols the Liberators drew additional duty out over the Western Approaches

to the United Kingdom. Vast men-and-equipment-laden convoys, spreading over hundreds of square miles of the Atlantic, had to be protected from the U-boats which

managed to sneak out of Biscay. Fast blockade runners from Japan tried to dash into Biscay ports at night. It was a busy, mostly monotonous life.

Not until December 1943 was variety to be introduced into the Navy's combat diet. Lone-wolfing out over the Bay one day, Lt. Stuart D. Johnston, USNR,

sighted 10 German destroyers, apparently operating as escorts for U-boats. The Lib flashed a message to Coastal Command headquarters and, within a few minutes,

depth charges were removed from bomb bays of planes hundreds of miles away in England and replaced with contact high-explosive bombs. In seven minutes one Navy

squadron had 10 planes airborne and heading for the DDs. Other Libs roared out to join the attack. Two British cruisers and their escorting destroyers raced

down the Channel. Through curtains of heavy flak the Libs ran in at zero altitude, broadside to the enemy, scoring several straddles and near misses and strafing

the decks with machine-gun fire. All the Libs came back, one with 100 flak holes in wing surfaces and fuselage. The battle ended in the sinking of four of the

Nazi craft by the British cruisers, Glasgow and Enterprise.

Eventually the Lib squadrons had their own base. Dunkeswell, the field from which they had been flying, was formally turned over to them by the British

and, other than remaining under Coastal Command operational control, they developed it according to American methods. Later, as the Biscay battle grew hotter

and the need for protecting shipping shuttling back and forth across the Channel to

-- 19 --

|

|

|

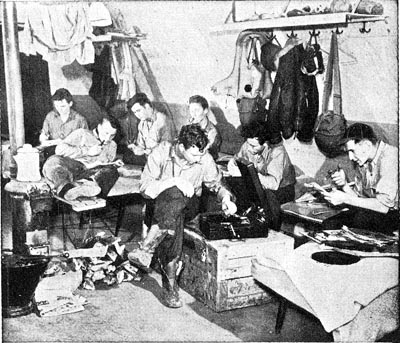

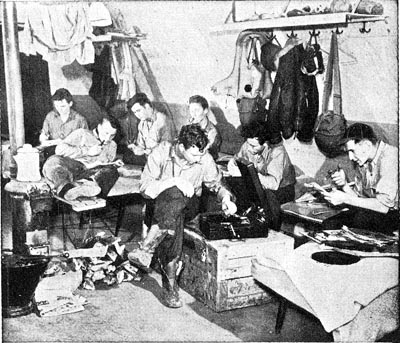

| AIR CREWMEN relax in Nissen hut quarters. Liberties were frequent, but they were at home only in their planes. |

|

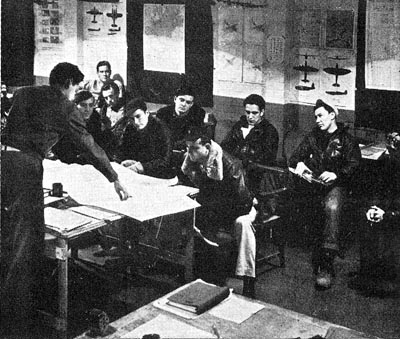

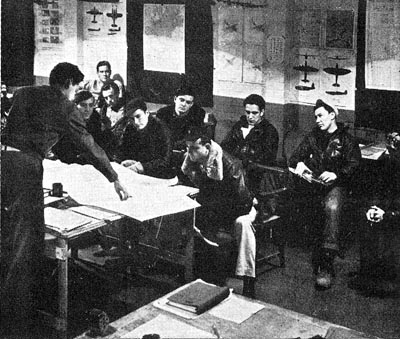

PRE-TAKEOFF briefing as to weather, convoys and signs of enemy is given Biscay flyers by intelligence officer. |

newly invaded France grew more important, two more squadrons - 107 and 112 - were added to the Navy's force and another base, Upottery - a mile from the

original Dunkeswell - was turned over to the Yanks.

Squadron 107 came with a hot reputation and maintained it until the end. Starting as Patrol Squadron 83 in December 1941 and using Catalina flying boats,

107 had operated from the mainland of Brazil and Ascension Island over South Atlantic patrol. During that time it changed to Liberators and eventually arrived

in England to fight with the other squadrons of Fairwing 7. Its final count of kills was nine U-boats destroyed, two probably sunk and 16 damaged.

Veteran of the European Theater, Bomron 103 once flew from Newfoundland but it served its last 21 months in Devonshire. Even during the final days of

the Reich it got two enemy subs, in March and April.

Originally known as Patrol Squadron 31, flying Catalinas from the Caribbean to Newfoundland, Bomron 105 sighted and attacked 10 enemy submarines and

destroyed two of them during its period based in England.

Another veteran of the Biscay patrols was Squadron 110. During 21 months operating from the United Kingdom its planes attacked 23 U-boats and even after

V-E day it scored a victory. Lt. Fred L. Schaum, USNR, a 110 pilot, accepted the surrender of U-249 and brought it into port, the first enemy submarine to

give up after the cessation of hostilities.

Last of the five squadrons to arrive in England was 112, an anti-U-boat outfit that had kept watch over the eastern Atlantic and Straits of Gibraltar to

close the Mediterranean to the enemy underwater boats. Early in 1945 it shifted to Upottery and from there participated in the destruction of another submarine.

Throughout their long, grueling watch the five squadrons were some what depleted by enemy action. Replacements arrived from the States to fill in the gaps

and enable Fairwing 7 to carry on. Some of the planes just disappeared. Others fell prey to the changeable weather. Still others were shot down by heavy U-boat

flak or the guns of the German fighters. But most of them took their toll before they were lost.

And so it will continue in the Pacific. Some of the squadrons are to be decommissioned. Pilots, navigators and gunners are to be retrained for new type

of work. They may fly search Privateers or heavies based in the Ryukyus or the Philippines and their targets may be small freighters instead of surfaced

submarines. But their long experience as air-borne warriors will stand them in good stead - their rigorous, courage-demanding experiences in the Atlantic

will make them that much more formidable against the dwindling sea power of the Japs.

|

|

|

| Official U. S. Navy photographs |

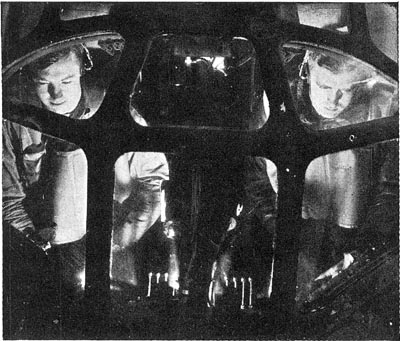

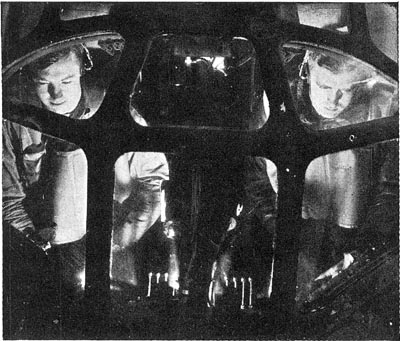

| PILOT AND CO-PILOT, their faces lighted by instrument panel, nose their Lib into the murky English sky. |

|

MISSION COMPLETED, plane commander, captain and navigator tell observations and action to intelligence. |

--20--

Table of Contents

Previous Section [3d Year: Waves Number 86,000] * Next Section [After The War - School?]