Both the Allies and the Axis began regrouping and preparing for the next stage of the Tunisian campaign as soon as Rommel had abandoned the February offensive. The Allies intended to press all Axis forces inside a firmly held cordon in the narrow northeastern corner of Tunisia, isolate them from Europe, and then split them into segments for piecemeal destruction. Operations to constrict the enemy within the limited bridgehead would consist of two major phases. First, the British Eighth Army (Gen. Sir Bernard Montgomery) would push northward along the coast through the Gabès narrows and central Tunisia beyond Souse. Second, Allied engineers would construct new airfields and reconstruct captured enemy airfields close to the new front so that increasing Allied air power could be used against the enemy with full effect in the final stage of the campaign.

The British Eighth Army's drive northward would be the main Allied effort in its first phase. The British First Army when it had regrouped was expected to engage only in small holding attacks along the northern front and, of course, to hold onto its avenues of approach to Tunis and Bizerte. The U.S. II Corps in central Tunisia would during this phase also play only an auxiliary role. While the Eighth Army attacked the Mareth and Chott Positions near Gabès, the II Corps was expected, by carefully timed, well prepared, and suitably controlled attacks, to seize dominating positions along the enemy's line of communications. These restricted operations would not only absorb enemy reserves which could otherwise be used against the British Eighth Army but would also, in the army group commander's judgment, advance the training of II Corps, increase its self-confidence, and improve its morale. He had no intention of employing II Corps to cut the enemy's line of communications by thrusting beyond the Eastern Dorsal onto the coastal plain, but only to threaten such action and thus attract enemy reserves to engage in defensive measures. The Eighth Army's attack on the Mareth Position would begin in the middle of March. The auxiliary operations in central Tunisia were adjusted to that schedule.1

Reorganizing the Allied Command

When General Alexander arrived in Algiers on 15 February to confer with the Commander in Chief, Allied Force, arrangements for his headquarters at Constantine were completed, his responsibilities defined, and his directive prepared.2 Headquarters, 18 Army Group, assumed principally those responsibilities previously discharged at AFHQ relating to the control of operations.

By close liaison, special staff visits, and a system of observation (called PHANTOM) and reporting over direct radio channels from the subordinate units in the field to army group headquarters, it undertook to achieve the necessary co-ordination between ground, air, and sea activities in the Tunisian area. Tactical air support was to be centrally controlled through air commanders with each British army and with II Corps, all under the higher command of the Headquarters, Northwest African Tactical Air Force. A naval liaison officer at 18 Army Group headquarters would furnish advice on naval problems to the ground commanders.

In Algiers, G-3, AFHQ, kept in close communication with General Alexander's command, and sent liaison officers on frequent visits. Army group controlled and coordinated the collection of intelligence by both the First and Eighth Armies, and by means of its own supplementary efforts was able to make full and accurate estimates of the Axis order of battle. General summaries and reports of interrogations of prisoners of war went directly to G-2, AFHQ, from forward collection agencies, with army group disseminating the resulting analyses. British troop training fell under its control but that of American troops was reserved for G-3, AFHQ. Logistical support, including transportation, remained outside the army group's province. Only the control over level of supply and assignment of priorities in delivery was exercised by army group.

Although it was an Allied headquarters with a certain number of American officers, 18 Army Group was predominantly British. At first most of its officers consisted of staff members of General Alexander's earlier command brought by airplane from Cairo. It was organized on British staff lines, with a list of about 70 at the outset, and over 100 before the end of March. The preparations for 18 Army Group's activation involved the removal of Headquarters, British First Army, from Constantine, to Laverdure, about 110 miles farther east, and closing of the AFHQ advanced command post at Constantine. The 18 Army Group occupied offices and billets thus vacated, and was ready for activation about 12 February, waiting only for the commanding general's arrival.3 His chief of staff was Maj. Gen. Sir Richard L. McCreery. Brig. L. C. Holmes was in charge of operations, and an American, Brig. Gen. William C. Crane, was his deputy.

On 8 March the 18 Army Group began by active direction in the forward areas to supplement the planning and co-ordination which it had hitherto undertaken.4 Although the regrouping which followed Rommel's retreat to the Eastern Dorsal had not yet been completed, the pattern was already apparent. The three headquarters directly subordinate to General Alexander were British First Army, U.S. II Corps, and British Eighth Army. The chain of command was to be in the form shown on the accompanying chart. The French XIX Corps' front was narrowed while most French troops were being rearmed and

Chart 2

Allied Command Relationships in the Mediterranean

March 1943trained, and General Koeltz remained under General Anderson's command.

General Alexander's survey of the Tunisian front and of his principal subordinates resulted in a decision to retain General Anderson, whom he then regarded as a sound soldier. His estimate of the performance by the U.S. II Corps commander during the recent battle was unfavorable, and he welcomed the possibility of a change for the better at that headquarters. The command of II Corps in future weeks had to be exercised by someone in whom Alexander had confidence and who, in turn, could claim the confidence of the American division commanders. Both General Ryder, whose 168th Infantry had been so badly affected by Fredendall's orders for its employment at Sidi Bou Zid, and General Ward, whose relief General Fredendall had proposed during the battle, lacked confidence in Fredendall's leadership, which they deemed responsible for assigning tasks and then prescribing both means and methods ill-adapted to their accomplishment; Fredendall, moreover, had precipitated a choice between himself and Ward, if either was to be retained. After an attempt at Headquarters, II Corps, at Djebel Kouif on 3 March to diagnose the state of the U.S. 1st Armored Division had revealed how much life and substance remained, and after General Alexander's estimate of General Fredendall had been taken into account, General Eisenhower determined to bring in a new corps commander, a conclusion in which he was confirmed by the information that his chief of staff, General Smith, his special representative, Maj. Gen. Omar N. Bradley, his former deputy chief of staff at the Advance Command Post, AFHQ, General Truscott, and his G-3, General Rooks, were able to furnish.

Maj. Gen. George S. Patton, Jr., whom General Eisenhower selected, was brought to Tunisia from I Armored Corps in Morocco to participate in operations for which he had been thirsting. He took command of II Corps on 6 March, bringing with him a new chief of staff, Brig. Gen. Hugh J. Gaffey, and other staff officers in case of need. His service in Tunisia was to be an interruption in his planning and preparation to command the American troops in the forthcoming invasion of Sicily. Most of his I Armored Corps staff officers were not required in Tunisia. General Bradley was designated to succeed him as soon as operations in southern Tunisia were completed, and was made deputy corps commander until Patton's retirement from Tunisia. This change was the major modification of the chain of command in the Allied Force.5

General Eisenhower's instructions to Patton defined his immediate task as the rehabilitation of the American forces in II Corps with all possible speed in order to make an attack already directed by 18 Army Group. Intensive training, re-equipping, reorganization, and application of all lessons thus far learned, and careful planning of the logistics of the attack, were to come first, along with an effort to instill in American forces a spirit of genuine partnership with the British forces. Patton was advised to train all combat forces, rather than engineers alone, in detection and removal of mines and in the proper use of mines for defensive purposes. He was also advised to

LT. GEN. GEORGE S. PATTON, JR., and General Eisenhower conferring at beginning of II Corps offensive, Tunisia, 16 March 1943.

demonstrate the fact that the 37-mm. antitank gun could knock out the German Mark IV tank with the latest ammunition. Eisenhower, with Patton's well-known personal courage in mind, then remarked, "I want you as a Corps commander, not as a casualty." And, he added: "You must not retain for one instant any man in a responsible position where you have become doubtful of his ability to do the job. . . . This matter frequently calls for more courage than any other thing you will have to do, but I expect you to be perfectly cold-blooded about it. . . . I will give you the best available replacement or stand by any arrangement you want to make."6

General Eisenhower's staff received a new G-2, a position held by a British officer in view of the extensive use of British sources of information in the Mediterranean. The change was prompted by the fact that excessive reliance on one type of intelligence leading to a misinterpretation of the enemy's intentions had contributed to the setback at Sidi Bou Zid. Brig. Kenneth D. W. Strong, a former British military attaché in Berlin, was sent from the United Kingdom by General Brooke to relieve Brig. Eric E. Mockler-Ferryman at Algiers.7

Ground Forces Reorganize

The reorganization of Allied ground forces was intended to include the formation of reserves at each level of command. The arrival in Tunisia of British 9 Corps headquarters and troops (Lt. Gen. Sir John Crocker), to be followed during March and early April by the British 1st and 4th Divisions, would facilitate the creation of reserves. But in the interval before their arrival, the policy was incompatible with current battle requirements and with the principle of keeping divisions intact, and was also hampered in execution by the process of sorting out all units into national sectors. General Alexander ordered the transfer into 18 Army Group reserve of Headquarters, British 9 Corps, British 6th Armoured Division, and British 78th Division. The scheduled shift was delayed to meet General Anderson's needs for infantry with which to push the enemy back from the hills north of Medjez el Bab, but by 12 March the reserve was established. General Keightley's 6th Armoured Division then passed under General Crocker's command and resumed the process of refitting with Sherman tanks, a process beginning when the enemy attacked at Sidi Bou Zid. First Army was forced to do without substantial reserves for the next six weeks, and required British 5 Corps to dispose its troops subject to a possible need to send reinforcements to the sector of French XIX Corps. Under the plan of 12 February, 18 Army Group had contemplated thinning out the front line in order to obtain reserves. Early in March they expected that the Allied front would be shortened by British Eighth Army's northward progress, enabling one American division then to be shifted from the extreme southern part of the U.S. II Corps area to the extreme north of British 5 Corps zone. The remainder of the II Corps would sideslip northward perhaps as far as the Pichon˝Maktar highway, while the French XIX Corps moved northward as far as the

Pont-du-Fahs˝Bou Arada road and its immediate approaches from the north.8

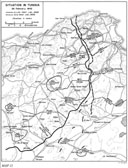

After the completion of the February battles, the Allied main line of resistance extended from Cap Serrat to El Ma el Abiod, running east of Sidi Nsir, Medjez el Bab, Bou Arada, Djebel Bargou (1266), Djebel Serdj (1357), Kesra, Sbiba gap, Djebel Semmama (1356), and Djebel Chambi (1544). It covered the lateral road from Djebel Abiod to Bédja, a great advantage to British 5 Corps, and the approaches to the plain of Tunis along either side of the Medjerda river. The front covered main gaps in the Western Dorsal from Maktar to Sbiba, and thence to the southwestern extremity of the mountain chain. (Map 13) The main landing fields in the Medjerda valley, the air landing grounds between Le Kef and Thala, and the airfields near Tébessa were protected, but the Thélepte airfields were left open to the enemy and were to be recaptured, if necessary, as a preliminary step in the forthcoming Allied offensive.

British 5 Corps (46th, 78th, and 6th Armoured Divisions) held the front from Cap Serrat to the mountains north of the Rebaa Oulad Yahia valley, and included within its zone Le Kef and Souk Ahras.

French XIX Corps, commanded by General Koeltz with headquarters at Djerissa, defended the next zone to the south. It comprised Divisions Mathenet and Welvert, with eight regiments of French infantry, two groups of Tabors, and the British 36 Brigade (reinforced). Its front extended into the mountains at a point northeast of Sbiba. The U.S. II Corps held the remainder of the front. The 34th Division, reassigned to II Corps, held the northeast sector and the 1st Infantry Division (after 27 February, the 9th Infantry Division), the southwest sector. Nearer Tébessa, the 1st Armored Division (and beginning 28 February, the 1st Infantry Division) prepared for the forthcoming offensive. Headquarters, II Corps, was at Djebel Kouif.9

The American divisions in II Corps required a certain amount of strengthening and reorganization. General Ryder's 34th Division needed to reorganize and rehabilitate the 168th Infantry, which had lost its commanding officer (Col. Thomas D. Drake) and much of its strength near Sidi Bou Zid. Col. Frederic B. Butler, from G-3, II Corps, became its new commander. General Ryder also sought the restitution to the 133d Infantry of its 2d Battalion, which was still being used in the AFHQ security detachment at Algiers, and requested thirty-six 105-mm. howitzers to replace the badly worn 25-pounder guns of the division artillery. The 9th Division, which was moving east under command of Maj. Gen. Manton S. Eddy during the Kasserine battles, lacked one of its regiments, the 39th Infantry. The 39th had been scattered since the Allied landings, doing guard duty along the line of communications, or at the Biskra airdrome, or fighting in Central Tunisia. The division had not yet fought as a unit and

Map 13

Situation in Tunisia

26 February 1943

remained in need of seasoning. The 1st Armored Division required replacement of severe losses in men and matériel. Furthermore, General Ward and others deemed this division too large. Its current core--six battalions of tanks, three of armored infantry, and three of armored artillery--was sufficiently large to invite endless detachment of units, and perhaps too cumbersome for the most efficient employment. Any such major change on the eve of the Allied attack was considered imprudent, but the problem was eventually met by modifying the table of organization. General Allen's 1st Infantry Division needed to recover from French XIX Corps the elements of the 26th Infantry still under General Koeltz's command while the rest of the division was concentrating for its first action as a division in Tunisia.10

The new commander of the II Corps attempted to transmit to his entire command the aggressive spirit with which he himself was animated, and to expedite preparations for the forthcoming attack. General Patton drove his principal subordinates and moved with restless energy throughout this area. His regime substituted military decorum for all traces of casualness, and required "spit and polish" as a preventive against carelessness. Some of Patton's methods to stamp his personal leadership on the entire II Corps seemed trivial to those on whom they were imposed. Changes which some might attribute to Patton's methods were perhaps also traceable to the lessons learned by troops in combat. The II Corps matured, working at its job, looking ahead more than it looked back, and needing more than anything else successes to boost its morale.11

The New Allied Air Command

Almost simultaneously with the activation of 18 Army Group late on 19 February, a new system of control over Allied aviation came into effect. At Algiers, the Mediterranean Air Command under Air Chief Marshal Sir Arthur Tedder began to function on 18 February, having at its disposal the Twelfth Air Force and Royal Air Force (RAF) Eastern Air Command, the Ninth Air Force, and three RAF commands--Middle East, Malta, and Gibraltar. These components were grouped by areas into the Middle East Air Command, Malta Air Command, and Northwest African Air Forces. The last of these was reorganized into functional organizations. General Spaatz, its commander, maintained an administrative echelon of his headquarters in Algiers but kept his operations headquarters at Constantine and made it a combined organization of American and British officers. The Northwest African Strategic Air Forces headquarters under General Doolittle controlled bombers and their fighter escorts from airfields near Constantine. The U.S. XII Bomber Command and two squadrons of British Wellington bombers continued to furnish the main long-range bombing strength. The Northwest African Tactical Air Force fell under command of Air Marshal Sir Arthur Coningham, who assumed control over the Allied Air Support Command (with General Kuter as deputy) a day or two before its redesignation, and established a combined operations headquarters adjacent to the new location of

Headquarters, First Army, at Laverdure.12 There General Alexander set up the advanced command post of 18 Army Group and shared facilities in a way which contributed to the maximum effectiveness of the Tactical Air Force, on the one hand, and the fullest use of First Army's resources on the other.13

Future collaboration between ground and air elements of the Allied Force was to benefit from the proximity of the respective commanders, but its fundamental basis was their past association in the Egyptian-Libyan desert, where they had together tested a successful doctrine of air support. Air Marshal Coningham controlled the U.S. XII Air Support Command and RAF 242d Group from the first, and resumed control over the Western Desert Air Force after it was transferred on 21 February to Northwest African Air Forces. These air commands were married to the major ground commands: XII Air Support Command with U.S. II Corps, RAF 242d Group with British First Army, and Western Desert Air Force with Eighth Army, as heretofore. So much for organization. What mattered far more than the fact of marriage was the nature of the marriage contract. The doctrine developed in the Western Desert of close union between air and ground forces had an eloquent and determined practitioner in the new commander of Northwest African Tactical Air Force.

The fundamental premises of the new program to be applied in Tunisia were that ground troops would benefit most from a lasting Allied supremacy over the enemy air force and that, in view of the limited Allied resources in air power, no operational air unit should remain unemployed, or be sent to a minor target. In accordance with these premises, control over tactical air units had to be centralized and missions had to be assigned to them by a commander fully conversant with their capabilities under varying military conditions, and thus able to determine priorities among competing projects. With such an arrangement, the offensive use of Allied air promised results cumulative in their value for Allied ground and air elements alike. Air umbrellas over ground troops were henceforth to be abandoned in favor of strikes on the bases from which enemy flights originated. The bombers making these strikes would be escorted by the fighter planes which might otherwise have put in hours of protective cover over ground troops without damaging the enemy.14 To summarize, the reorganization of 19-20 February 1943 was destined, through use of the ground-air doctrines tested in Libya, to promote by painful but inexorable steps the achievement of Allied air supremacy in Tunisia.15

In addition to the Northwest African Strategic and Tactical Air Forces, General

Spaatz's command included the Coastal Air Forces (controlled from Algiers in conjunction with the headquarters of the Naval Commander in Chief, Mediterranean), the Training Command, the Air Forces Service Command, and a Photographic Reconnaissance Wing.

The new air organization, particularly the Tactical Air Force, set about preparing airfields at sites appropriate for the expected pattern of ground operations, and establishing a radar warning and control system with which to apply new principles of air support. The mountains seriously impaired the effectiveness of radar, while the lack of telephonic communication between dispersed installations was likewise a handicap. Radio communication had to make up for the deficiencies in wire lines.

By 11 March, an outline plan of air operations in three successive phases was ready. Headquarters, 18 Army Group, and Tactical Air Force were then encamped near Aïn Beïda, from which they could cooperate during the imminent operations at the Mareth Position. The XII Air Support Command and RAF 242d Group were expected to make successive shifts onto new or improved airfields nearer the coast. A tactical bomber force of light and medium bombers was assembled and organized in the vicinity of Canrobert, northwest of Aïn Beïda. The XII Air Support Command prepared to concentrate at Thélepte, where the existing fields, once reoccupied, would be improved and supplemented, and like that at Youks-les-Bains, would be stocked with enough matériel to provide a surplus for the Western Desert Air Force's use when it came north. The airfields at Kalaa Djerda and Sbeïtla were to be improved, the former for the use of bombers. The Western Desert Air Force was expected to devote itself independently to supporting British Eighth Army in the main action. XII Air Support Command and RAF 242d Group were to assail the enemy air forces, carry out tactical reconnaissance, and assist night bombing on the line of communications.

Once Gafsa had been taken by the U.S. II Corps, and while the British Eighth Army was closing in on Gřbes, a second phase of air operations was envisaged in the air outline plan of 11 March. It would have two aspects. A shift eastward and northeastward by those engaged in airfield construction, radar erection, and supply would be paralleled by interference with the Axis air movement up the coast. In this phase, the operations of XII Air Support Command and Western Desert Air Force would have to be co-ordinated, and the latter would find airfields and supplies ready for it near Gafsa and at Thélepte. Preparations would be completed for the use during the final stage of airfields in the area from Souk el Arba and Souk el Khemis to Le Kef, Le Sers, and Thibar. (See Map VI.)

Air Marshal Coningham held a commanders' conference at Canrobert on 12 March at which it was agreed that once the battle for the Mareth Position had begun, XII Air Support Command and RAF 242d Group would attempt round-the-clock strikes on enemy airfields near Gabès. Western Desert Air Force might thus retain air supremacy over the battle area with lighter opposition and with greater capacity to engage ground targets in co-ordination with the Army elements. As the day for the initial Allied operations arrived, intermittent bad weather reduced the number of air strikes on enemy landing fields. They were begun on 13 March and taken up from time

to time by units of the Strategic Air Force as well as the Tactical Air Force.16

Allied Preparations in the Communications Zone

Like the forward area, the rear was reorganized and strengthened for the resumption of the Allied offensive in March. The accumulation of forces preparing for the eventual invasion of Sicily augmented the total number of military personnel with a corresponding increase in the complexity of the agencies which supervised and supported combat troops. Algiers in particular was crowded with American and British personnel in addition to members of the French civil and military establishments. The process of Allied military build-up in Algiers had begun long before the planning for March. AFHQ filled up the Hotel St. Georges, the Hotel Alexandra, and other buildings which were converted to office space, and spilled over into several other buildings; it also occupied several hundred different officer billets. The troops assigned or attached to the headquarters command, and other units quartered temporarily in the vicinity of Algiers, added to the Allied military traffic. Antiaircraft batteries and smoke projector units, car and truck companies, military police, signal communications, postal and radio censorship units, and the workers engaged in servicing records--all the varied and extensive aspects of the modern great army headquarters contributed to the Allied military population in Algiers in ever-increasing numbers.

The North African Theater of Operations, U.S. Army (NATOUSA), was activated at Algiers on 4 February 1943, to handle the administrative concerns of the growing American Army forces in the area, matters which were not properly a subject for Allied action. At first, like the commanding general, most of its military personnel doubled as both Allied Force and theater officers. Later, when some whole sections of AFHQ were transferred to comparable staff sections of NATOUSA, the total strength of the staffs in Algiers was still unaffected. But in the course of time, largely as a result of a determination to undertake more and more projects, the total grew. A substantial number of the units of AFHQ were operational rather than supervisory agencies. They pursued their projects with great energy, intent on doing everything possible to make them succeed. By April, AFHQ exceeded 2,000 officers and enlisted men, illustrating how military, like civil administrative establishments, tend to grow and rarely to dwindle.17

The supply organization in the communications zone with which to meet the requirements of the March offensive was created during the preceding month. Brig. Gen. Everett S. Hughes, who had been engaged in ETOUSA on the logistical problems connected with Operation TORCH, arrived on 12 February in Algiers to be deputy theater commander and commanding general of the communications zone. An Eastern Base Section at Constantine to supply the requirements of U.S. II Corps was constituted on 13 February under command of Col. Arthur W. Pence and opened on 27 February. With the Atlantic Base Section

at Casablanca and the Mediterranean Base Section at Oran, the Eastern Base Section came under the direct control of General Larkin as Commanding General, Services of Supply, NATOUSA. The flow of matériel to General Patton's corps was to occur within the broader pattern of Allied buildup for the operations in Tunisia, the campaign being planned for Sicily, and perhaps additional undertakings in the Mediterranean. Supplies for II Corps had to be forwarded in a manner minimizing interference with the British Line of Communication to First Army, which in January had passed to the control of AFHQ from Headquarters, First Army.

Maj. Gen. J. G. W. Clark (Br.), commanding No. 1 Line of Communications Area from headquarters at Sétif, with sub-areas at Algiers, Bougie, Philippeville, Bône, Constantine, and Souk Ahras, reported to Maj. Gen. Humfrey Gale (Br.), Chief Administrative Officer, AFHQ.18 With the three American base sections and the coordinating Headquarters, Services of Supply, NATOUSA, reporting to the deputy theater commander while the British Line of Communication reported to the chief administrative officer, and with a separation of American and British maintenance impossible, and indeed in many respects undesirable, the problems were met as they arose by steady co-operation between Generals Hughes and Gale. The disproportionately low ratio of service to combat troops with which the early operations in Northwest Africa had been undertaken was raised during the first four months of 1943.19

Allied plans in outline for logistical support were sketched at AFHQ on 27 February in a conference over which the chief administrative officer, General Gale, presided, and at which Maj. Gen. C. H. Miller (Br.) of 18 Army Group described the prospects. First Army's supply base would be at Bône, while II Corps would draw on the new Eastern Base Section at Constantine.20 Each army would be responsible for deliveries forward of these advanced bases. While First Army would maintain the air elements in its northern area, Line of Communication, Third Area Service Command, near Constantine would supply those in the southern sector and along the Constantine˝Tébessa axis. In addition to the motor transport allotted to each army and for AFHQ reserve, a special reserve for British Eighth Army was to be accumulated in the Constantine area on a scale to be determined by 18 Army Group. Participation by British troops and air units in operations to the south would be assisted by stocking gasoline and ammunition at accessible points. The principal maintenance center for tanks was to be at Le Kroub, near

UNLOADING P-38 FIGHTER PLANES, for the French Army, Casablanca, 13 April 1943. Note Arab helpers on the dock.Constantine, with facilities at Bône for servicing Churchill tanks.21

By March, the expansion of Allied logistical support which had been envisaged since the end of December began to reflect the result of the arrangements then made. The main ports of Casablanca and Oran, and the satellite ports near them, stepped up their operations. The Sixth Port of Embarkation (Mobile) at Casablanca and the Third Port of Embarkation (Mobile) at Oran were reinforced by two and three port battalions, respectively. Each port employed several hundred Arab laborers on the docks

and also contracted with French companies to assist in unloading operations. For the Eastern Base Section at Constantine, the port of Philippeville was made available. It was dredged to a twenty-two-foot depth, which permitted four partially loaded Liberty ships and two coasters to discharge cargo simultaneously; the port was equipped with cranes, hoists, and other cargo-handling machinery which expedited the unloading process.22 On occasion, LST's could run from Oran to Philippeville with replacement tanks which then went on transporters over the road to the vicinity of Tébessa. For the operations in April, the deeper port of Bône was also to be shared with the British Line of Communication and was greatly increased in cargo-receiving capacity. But in March, the 91,000 tons which passed through Philippeville in addition to that brought by rail and highway from the west met the requirements of the U.S. II Corps and the XII Air Support Command, and made possible the accumulation of reserves on which the British Eighth Army could shortly draw.23

Railroad and highway transportation across French North Africa were both greatly expanded by March through the work of engineers and the Transportation Corps, U.S. Army. A very large requisition for railroad rolling stock which was made when the Allied drive on Tunis failed in December began to be filled in March, by which time managing and operating personnel for this equipment had also arrived. Before the end of April, forty-three trains, averaging over 10,700 tons daily, were passing through Constantine toward the combat zone.24

Expanded highway transport was essential for the accumulation of matériel for the Allied campaigns of the spring. A special convoy arriving on 6-7 March brought more than 4,500 two-and-one-half-ton trucks into Casablanca and Oran.25 Other convoys brought more than 2,000 per month. Great assembly plants processed the twin-unit-packed crates of trucks. Companies and battalions of truck drivers to operate them were combed out of various units. One battalion which was formed in the Casablanca area had its trucks loaded with high-priority cargo, and, within a week of arrival, started in convoy to Ouled Rahmoun about 1,000 miles away. The battalion arrived there on 23 March with an excellent record. Road maintenance, traffic control posts and stations, and good organization stepped up highway traffic until, late in March, the average number of vehicles reaching Orléansville daily eastwardbound was 600; in the area of the Eastern Base Section, some 1,500 trucks and 4,500 troops were supplementing the railroad. From Ouled Rahmoun and Bône to Tébessa, the daily transportation then came to 500 tons or more.26 Clearing the ports

and railroad terminals and conveying supplies from depots to dumps required the service of hundreds of trucks in addition to those used in the longer convoys. Including local hauling, the Eastern Base Section recorded movement in April of a total of 51,541 truck loads amounting to almost 84,000 tons.27

While the vast bulk of overland traffic was eastward bound, salvaged matériel began to flow back for reconditioning and repair. At Oran and Casablanca, the outward-bound cargo transports were loaded with French North African products such as cork and phosphates, or with scrap iron, until their return loads were almost half as heavy as those which they had brought.

Substantial numbers of the personnel brought to French North Africa in the spring troop convoys came there to prepare for the invasion of Sicily or to join the U.S. Fifth Army. Much of the matériel being unloaded at the ports in March was intended to remain in Morocco and western Algeria, either to be used by troops in the communications zone or to sustain the French and native civilian population. Even so, the volume of supplies which kept arriving at Casablanca, Oran, and the ports near them dwarfed the total which was reaching Tunisia from the northeast to support the Axis forces.28 It was apparent by the end of March that in Tunisia the Americans alone were being supplied at a higher rate than all the Axis forces there.29 Before the Allied offensive in March, replacement depots ("repple-depples") were established near Oran and Casablanca with a total capacity exceeding 11,000.30

Preparations by the French

The rearmament of the French under Giraud to which the President had agreed in principle at Anfa, and which had required much subsequent negotiation, began to take form while the Allied forces in Tunisia reorganized. The main problem was that of cargo space and convoying, although other difficulties also had to be overcome. In accordance with a supplementary understanding, a special convoy of fifteen ships loaded with matériel for the French was to be en route from the United States by the time the Allies began their March offensive in southern Tunisia. Ten more ships would be sent later.

The weapons and equipment to arrive in April would, when distributed to French units, make ready two infantry divisions, two armored regiments, three tank destroyer battalions, three reconnaissance battalions, twelve antiaircraft battalions (40-mm.), and ten truck companies. Beginning a little later, American planes would start arriving at the rate of 60 per month until they reached a total exceeding 200 fighters, dive bombers, and transports. Training of aerial gunners could commence in April and of pilots in June, at the rate of 100 for each of the first two months and 50 per month thereafter. Within French North Africa, training in the operation and maintenance of American

matériel would begin before these shipments arrived.

This program was considerably slower and smaller than the one Giraud had anticipated after sampling the President's buoyant encouragement in January at Casablanca. The curtailment actually resulted from the many competing claims upon American munitions and upon Allied shipping, but Giraud was encouraged to believe that by more liberal administrative policies in French North Africa he could expedite the rate at which American arms would be delivered to his forces. Although Giraud may indeed have suffered some loss in prestige from the dragging pace of French rearmament, his political difficulties arose mainly from his disdain for such questions, his belief both that the fundamental objective of military success over the Axis powers transcended all other considerations, and that any attention which he had to give to politics constituted an intrusion on his concern with more important affairs. He leaned heavily on French political advisers and his political decisions were subjected to the close scrutiny of the Allied commander in chief, such scrutiny being exercised with the aid of Mr. Robert Murphy and Mr. Harold Macmillan. The consistent position of the Allied leadership was that conditions of political tranquillity conducive to immediate military advantage must be maintained, and that these conditions should, if possible, be made to prevail without forfeiting French unity or general future support by the French when the main Allied effort would be made on the soil of Continental Europe.31

Giraud was finally persuaded, after himself sensing political opinion in the French armed forces under his control, that unity on any terms acceptable to General de Gaulle could not be soon achieved. He therefore proceeded to revamp his government while reconstructing the French Army with American arms. On 6 February and 14 March 1943, under Allied guidance, he announced the termination of Darlan's Imperial Council of provincial governors and of all the fictitious ties with Vichy. He himself assumed complete power over all civil and military authorities in French North and French West Africa. He declared that he would be advised by a War Committee in which the former members of the Imperial Council would be joined by other Frenchmen. Political prisoners and refugees were to be released from detention at once. Organizations of Vichy origin, like the Service d'Ordre Légionnaire, were to be suppressed. Administrative councils representing French and native groups would be formed to advise and assist the governors of all colonies and municipalities. He instigated a trip to London by one of de Gaulle's leading adherents in Algiers, Professor René Capitant, to furnish the Fighting French leader with a trustworthy, first-hand report of conditions. Giraud became increasingly receptive to liberal advice, including that from M. Jean Monnet, who went from the United States to assist him in Algiers. On the eve of the Allied offensive, he thus had taken a considerable step away from an authoritarian attitude toward French political republicanism, and had also opened negotiations through General Catroux for a merger with the Fighting French in London.32

Table of Contents ** Previous Chapter (24) * Next Chapter (26)

Footnotes

1. Alexander, "The African Campaign."

2. (1) Note of War Room Mtg, 22 Jan 43. AFHQ G-3 Ops 58/2.1, Micro Job 10C. Reel 188D. (2) AFHQ Opn Memo 30 (rev.), 18 Feb 43. (3) Dir, 17 Feb 43, printed in Alexander, "The African Campaign." App. B, pp. 885-86.

3. (1) 18 A Gp Staff Appointments List, 27 Feb 43 and Mar 43. AFHQ Micro Job 10A, Reel 6C. (2) History of Allied Force Headquarters and Headquarters NATOUSA, December 1942-December 1943, Pt. II, pp. 110-16, 324-26. DRB AGO. (3) Memo, G-3 AFHQ for CofS AFHQ, 30 Jan 43, sub: A Gp Hq. AFHQ Micro Job 10A, Reel 6C. (4) Alexander, "The African Campaign." (5) Intervs, Alexander with Mathews, 10-15 Jan 49. In private possession.

4. First Army Opn Instruc 20, 7 Mar 43. DRB AGO.

5. (1) Intervs, Alexander with Mathews, 10-15 Jan 49. (2) CinC AF Diary, 1-5 Mar 43. (3) Msg 4267, Eisenhower to Marshall, 4 Mar 43; Msg 4580, Eisenhower to Marshall, 5 Mar 43; Msg 3471, Marshall to Eisenhower, 8 Mar 43. Smith Papers. (4) Gen Ward, Personal Diary, 1-5 Mar 43. In private possession. (5) Omar N. Bradley, A Soldier's Story (New York, 1951), pp. 41-48.

6. CinC AF Diary, 7 Mar 43, Bk. V, pp. 270-71.

7. (1) Eisenhower, Crusade in Europe, p. 147. (2) CinC AF Diary, 20 Feb 43, Bk. V, p. A-236. (3) Msg 1977, FREEDOM to TROOPERS, 20 Feb 43; Msg6 5014, TROOPERS to FREEDOM, 20 Feb 43. ETOUSA Incoming and Outgoing Cbls, Kansas City Rcds Ctr.

8. (1) 18 A Gp Opn Instruc 6, 6 Mar 43, supplied by Cabinet Office, London. (2) First Army Opn Instruc 19-22, 24 Feb˝8 Mar 43. DRB AGO. (3) Msg, USFOR to FREEDOM, 2135, 26 Feb 43. ETOUSA Outgoing Cables, Kansas City Rcds Ctr.

9. (1) First Army Opn Instruc 19, 24 Feb 43. DRB AGO. (2) First Army Sitrep 123, 28 Feb 43; 18 A Gp Cositrep 7, 26 Feb 43. AFHQ CofS Cable Log. (3) DMC Jnl, 28 Feb 43. (4) By 17 March French XIX Corps had a strength which approximated 53,800, including British units in the corps troops. See 18 A Gp SD 1, 17 Mar 43. AFHQ Joint Rearmament Committee 370/001, and also in AFHQ G˝3 (Ops) 37/13, Micro Job 10C, Reel 15 7F.

10. (1) Msg 1233, Adv AFHQ (Truscott) to AFHQ (Eisenhower), 1 Mar 43. AFHQ CofS Cable Log. (2) Ltr, Truscott to Ward, 2 Mar 43. In private possession.

11. Bradley, A Soldier's Story, pp. 44-45.

12. On 19 February he announced that he had instructed all his command "to cease defensive operations involving cover for troops except in special circumstances and with his approval." Offensive action to maximum capacity should replace such use. Msg AI 24, Allied ASC 18 A Gp to First Army et al., 19 Feb 43. AFHQ CofS Cable Log.

13. (1) Intervs, Alexander with Mathews, 10-15 Jan 49. (2) Craven and Cate, The Army Air Forces, II, 161-64. (3) Info supplied by Air Ministry, London.

14. FM 31-35, Air-Ground Operations, 9 Apr 42.

15. (1) Craven and Cate, The Army Air Forces, II, 136-37, 164-65. (2) See also Col. Kent Roberts Greenfield, Army Ground Forces and the Air-Ground Battle Team, Including Organic Light Aviation, AGF Hist Sec, Study 35, 1948, pp. 1-5, which shows how far Army Air Forces doctrine had already gone toward integrating the effort of air and ground forces by 9 April 1942.

16. (1) Craven and Cate, The Army Air Forces, II, 167-75. (2) Info supplied by Air Ministry, London.

17. (1) Hist of AFHQ and NATOUSA, Pt. II. pp. 240-45. (2) General Eisenhower's directive as theater commander is Message ZRH-2624, AGWAR to FREEDOM, 20 February 1943. OPD Msg Ctr File.

18. (1) Hist of AFHQ and NATOUSA, Pt. II, pp. 175-76, 215-17. (2) Trans Sec EBS NATOUSA Hist Rcds, 22 Feb˝30 Apr 43. OCT HB. (3) Col. Creswell G. Blakeney, ed., Logistical History of NATOUSA-MTOUSA, 11 August 1942 to 30 November 1945 (Naples, Italy, 1946), p. 23.

19. The problem remained difficult at Casablanca at the time of a visit by the Assistant Secretary of War, John McCloy. McCloy reported this situation in a memo for Maj. Gen. Wilhelm D. Styer, 22 March 1943. General Handy's comments are found in his memo for the Commanding General, Army Service Forces (Attention: General Styer), 27 March, subject: Report of the Assistant Secretary of War on conditions in Casablanca. OPD 381 Africa (1-27-43), Sec 2, Item 89.

20. U.S. II Corps was under First Army until 2400, 8 Mar 42, thereafter under 18 Army Group. Info supplied by the British Cabinet Office, London.

21. (1) Notes of AFHQ Log Plans Sec Mtg (signed by Lt Col J. C. Dalton), 27 Feb 43, dated 1 Mar 43, sub: Admin policy for development of adv opns base in Tunisia. OCMH. (2) 18 A Gp Admin Instruc 1, 4 Mar 43, supplied by Cabinet Office, London. (3) Plans in late January set the daily tonnage estimated for the troops in Tunisia as follows:

1-15 March 16-30 March Total 3,675 4,205 First Armya 1,900 2,380 Twelfth Air Forceb 1,155 1,205 Line of Communicationc 620 620 a Including U.S. and French forces under First Army command and RAF in First Army area.

b East of Algiers.

c Including RAF not in First Army area and French forces on line of communication

Source: Memo, CofS AFHQ for CG First Army, 29 Jan 43. sub: Orgn and prep for renewal of offensive. AFHQ G-3 Ops 58/2.1, Micro Job 1OC. Reel 188D.22. Trans Sec EBS NATOUSA, 22 Feb˝30 Apr 43, pp. 7-8. OCT HB.

23. Ibid., p. 22, citing rpt of Maj Arthur G. Siegle, OCT, 9 Apr 43.

24. (1) Memo, Brig Gen Carl R. Gray, Jr., for Deputy Chief of Trans NATOUSA, 1 May 43, cited in H. H. Dunham, U.S. Army Transportation and the Conquest of North Africa, 1942-1943, Hist Unit OCT, Jan 45, p. 208. (2) Bykofsky and Larson, The Transportation Corps: Operations Overseas.

25. Memo, Lt Col Edwin C. Greiner for Brig Gen Robert H. Wylie, 3 Feb 43, sub: Cargo for UGS 5-A; Memo, Gen Wylie for Gen Styer, 25 Feb 43, sub: Cargo shipped on UGS 5½. OCT HB.

26. (1) Trans Sec EBS NATOUSA Hist Rcds. 22 Feb˝30 Apr 43, p. 12. (2) Dunham, U.S. Army Transportation and the Conquest of North Africa, 1942˝1943. Hist Unit OCT, Jan 45, pp. 263, 266, 268.

27. Ibid., p. 269.

28. In March, 146,000 tons were discharged in Moroccan ports and 220,000 tons in Oran, Arzew, and Mostaganem. Chiefly by reshipment, 91,000 tons came into Philippeville.

29. Eastern Base Section was getting 1,000 tons per day by truck alone into Tébessa, Axis importations in March came to less than 29,267 tons. No account is taken in this comparison of what the British First and Eighth Armies were then obtaining. (See Appendix B.)

30. Maj Gen William H. Simpson, Obsr's Rpt, 27 May 43. AGF 319.1/58.

31. (1) CinC AF Diary, Bk. V, pp. A-258-59. (2) Giraud, Un seul but: la victoire, p. 121. (3) Msg, FREEDOM (Murphy) to AGWAR (Hull), 13 Dec 42. AFHQ Micro Job 24, Reel 78D.

32. Georges Catroux, Dans la bataille de Méditerrnée; Égypte, Levant, Afrique du Nord, 1940-1944 (Paris, 1949), pp. 325-30, 340-49.