Chapter VI

The MARS Force and the Burma RoadWhile the Chinese divisions in north Burma had been pushing the Japanese out of the upper reaches of the Shweli valley and so off the trace of the almost completed ground line of communications to China, the moment had been approaching when the small American force in Burma was to receive its greatest test. It was given the mission of striking across the lower end of the Shweli valley to the old Burma Road and hastening the advance of the Chinese forces against the Japanese still on the upper trace of that road. The significance of this mission was that as long as substantially intact and battleworthy Japanese forces remained in north central Burma neither the operation of the new Ledo Road nor the flank and rear of the British forces now driving deep into Burma could be secured. Nor could the three American-trained Chinese divisions in Burma and the MARS Force be released to reinforce Wedemeyer. It was believed that the MARS Task Force, acting as a goad on the flank of the Japanese line of communications, could make a significant contribution to victory, while its performance would show whether the lessons of the GALAHAD experiment in long-range penetration warfare had been learned.

Marsmen Prepare for Battle

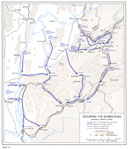

Though pushing the Japanese off the trace of the Burma Road tended to overshadow events elsewhere, it was only part of a larger operation, CAPITAL. Phase II of CAPITAL called for taking the general line Thabeikkyin-Mogok-Mongmit-Lashio by mid-February 1945; operations looking directly toward the completion of that mission had been under way simultaneously with those to clear the road. Sultan's current plan called for the forces under his command to swing east like a closing gate. To the north, this maneuver had pushed the Japanese off the trace of the road to China, but the rest of the swing was still to be made. MARS Task Force, the Chinese 30th Division, and the Chinese 114th Regiment had still to move east and cut the Burma Road below the Namhkam-Wanting area, the Chinese 50th Division had to take Lashio, and the British 36th Division had to cross the Burma

Map 10

Securing the Burma Road

January-March 1945

Road south of Lashio. This swing would sweep the Japanese from the area north of CAPITAL's Phase II line.1 Meanwhile, the 38th Division (-) of the Chinese New First Army would be operating to the north in the Namhkam-Wanting area. The fighting in the northern part of the NCAC front, where NCAC's divisions had driven northeast to link with the Y-Force and break the blockade of China, has been described.2

The work of the rest of NCAC's forces, which did not reach its climax until February 1945, after the Ledo Road had gone into operation, developed south of the Shweli valley area, in and a little to the southeast of the triangle Namhkam-Mong Yu-Namhpakka. The Chinese forces from Burma and China, CAI and Y-Force, had met in the vicinity of the apex, at Mong Yu. The west side of the triangle was the Shweli valley, with Namhkam at its western corner. Forming the eastern side of the triangle was the Burma Road, on which were Mong Yu and Namhpakka. (Map 10)

NCAC believed that if MARS Task Force would thrust across the base of the triangle to the Burma Road, thus placing it closer to the locally well-known town of Lashio than were the Chinese, the latter might well be roused to emulate it through considerations of face. MARS would, it was hoped, spur the Chinese to greater activity in their operations.3

In deciding where to reach the Burma Road, Sultan rejected a suggestion, advanced by Easterbrook, the commander of the 475th Infantry, and adopted by General Willey, that MARS cut the Burma Road at a suspension bridge about twelve miles south of Namhpakka. A good trail led to the spot, the hills west of the road were within machine gun range of its traffic, and the Japanese could not easily bypass a roadblock there. But Sultan ruled otherwise. He did not think the Chinese would support a venture so deep into Japanese territory, and noted that the area did not offer a good site for a landing strip. He preferred the Ho-si area, farther north on somewhat flatter ground. But Ho-si had disadvantages, for there the Burma Road is beyond machine gun range from the ridge paralleling the road on the west.4 There were also secondary roads in the hills to the east, by which the Japanese could escape.

The first step toward blocking the Burma Road would be the forward concentration of the whole MARS Task Force, which meant bringing up the 124th Cavalry to join the 475th. Since the 124th did not arrive at Myitkyina until late October 1944, it was not until December that its commanding officer, Col. Thomas J. Heavey, and NCAC thought it ready for the long march to combat. On 16 December the 124th moved south in an administrative march,

MULE SKINNERS AND PACK ANIMALS of the MARS Task Force plod through the hills toward the Burma Road, January 1945.to proceed to the Bhamo area and there receive further orders. Five days later MARS headquarters followed, and reopened at Momauk.5

Supply arrangements revealed how completely the campaign had come to depend on air supply. The 124th was to report drop field locations forty-eight hours in advance; as they left camp the men would carry three days' rations and minimum combat loads of ammunition. Animal pack transport, to face the hills ahead, was heavily relied on, though a few trucks had been improvised from the derelicts that dotted the Myitkyina landscape.6

As they left Myitkyina, the men of the 124th revealed in little ways that they had been a cavalry regiment, still felt like a cavalry regiment, and were walking to war though no fault of theirs. Many of the troopers wore their old high-top cavalry boots, cut down an inch or two. Here and there in the columns were small two-wheeled carts, improvised by the men, and pulled

by ponies and little Burmese horses that the horse-wise 124th had enlisted for the duration. When called into federal service the 124th had been a Texas National Guard regiment. Transfers had diluted it, but 27 percent of the troopers were Texans.7

Marching along, the 124th passed through a settled area of Burma, part teak forest, part bamboo jungle with village clearings, and part rice paddy. The Burmese, from several tribes and peoples, would appear during breaks and bivouacs to barter or sell their chickens, eggs, rice, and vegetables. They rarely begged, unlike the Indians with their eternal cry of "baksheesh, sahib," nor were they endlessly persistent like the Chinese troops, but traded quietly and courteously. Sometimes the troopers descended on unwatched garden plots. Foraging and cooking, finding water, the occasional novelty of a pagoda, the problems of getting a good night's sleep and improvising a good meal, varied the days of slogging through dust and heat until the 124th reached Momauk, about six miles east of Bhamo. The hills were at hand, the Japanese were in them somewhere, the shakedown march was over.8

While the 124th was marching toward Momauk, the 475th and its supporting elements (the 612th Field Artillery Battalion, 31st, 33d, and 35th Pack Troops, 44th Portable Surgical Hospital) had been clearing the Japanese from the vicinity of Tonkwa. By Christmas Day it was apparent the Japanese had left the area,9 and as soon as elements of the Chinese 50th Division should take over in the Tonkwa area the 475th would be ready to join the 124th. When it did, the 5332d would operate as a brigade for the first time. Originally, MARS was to have been an American-style division, composed of the two U.S. infantry regiments and the Chinese 1st Separate Regiment. The concept was fading, for the same order that directed the 124th and 475th to assemble kept the Chinese regiment in NCAC general reserve.10 The 5332d would assemble in the Mong Wi area, within striking distance of the Burma Road. But between the two regiments and Mong Wi lay the Shweli River, and some of the roughest mountain country in north Burma.

Over the Hills and Through the Woods

Because Tonkwa is only some forty-five miles from Mong Wi, the 475th faced a shorter march than did the 124th, and was also closer to the mountains, two ranges of which, on either side of the Shweli, stood between it and Mong Wi. As 1944 closed, elements of the Chinese 50th Division were already across the Shweli on their way east, so the 475th would not have to

worry about an opposed crossing but could follow the Chinese over the vine and bamboo bridge the 50th had built. On New Year's Eve the American infantry left bivouac. With them were 220 replacements that had been flown to the Tonkwa area and so began a rough march without the hardening their comrades had received during the journey south from Myitkyina.11

So close is Tonkwa to the mountains that the 475th found the trail rising steeply on the first day's march east. Like a crazily twisted drill it bored its way farther east and ever higher. In some places it was fifteen to twenty feet across; in others, just wide enough for a man and a mule. As they rounded the turns, the men would peer ahead and look out across the valleys to where lay row on row of hills, like the waves of a frozen sea. Trees were everywhere. In flat places carved by erosion, the Burmese had cut and farmed terraces, and little villages clung to the mountains like limpets to a rock.

Because existing maps were unreliable, so that map reconnaissance could not locate water and bivouac areas, and because the sheer fatigue of climbing the steeper slopes was formidable, march schedules went out the window, or rather, down the mountain side, with quite a few steel helmets and an occasional mule. Halts were a matter of common sense leadership at platoon or company level.

The march was tactical but no Japanese were encountered, though rumor of their nearness kept the men alert. The Chinese had passed that way before, while a screen of Kachin Rangers was preceding the American column. Speaking the local dialects and carrying radios and automatic weapons, the Kachins were an excellent screen which masked the MARS Task Force while reporting anything that might be suspicious.

The 124th also found the mountains worse than it had expected. Though there had been four organized attempts to lighten the baggage load, and much was left behind at Momauk, still, when two days' march from that village the men began their climb, they found that the steep incline forced them to jettison cargo in earnest. The little two-wheeled carts made with such effort and ingenuity were no help; the trail was too much for them. The Burmese must have thought the lightening process a bonanza of cooking utensils, boots, underwear, spare fatigues, paper, and so forth.

For the 475th in the lead, crossing the 400-foot wide Shweli was not too hard. The bridge built by the Chinese some weeks before still stood, a triumph of Oriental ingenuity, with bundles of bamboo for pontons and vines for cable. The Shweli was beginning to tear it apart, but work parties from the 475th kept it operable. Once on the far side, the 475th found its march more difficult than before. The mountains were steeper and higher.

BAMBOO BRIDGE OVER THE SHWELI RIVERBeing higher, they were often hidden by cloud, so that air supply was impossible and the men went hungry. Just as they were approaching Mong Wi, and the 124th was about to cross the Shweli, rain began. Trails became extremely slippery and hazardous, and even the mules sometimes slid into ravines. That day, 6 January, the 2d Battalion of the 475th evacuated twelve men as march casualties.

The rain fell on the 124th as it began descending to the Shweli. The trail was over a fine red clay; when soaked, the footing became quite slippery. Men and mules skidded right on down to the river edge, in a mad muddy slide that mixed the comic and the hazardous. Colonel Heavey would have preferred to cross elsewhere, but after the 124th had lost 4 January in looking for crossing points and waiting for an airdrop, and a series of radios had been exchanged between Heavey and NCAC, the 124th was told to cross where it could, providing it reached Mong Wi on schedule. That time limit committed it to the muddy slide and the Chinese bridge.

Thanks to the rains, the Shweli was now in flood and pulling the bridge

apart. Considerable rebuilding was necessary, while the bridge's flimsy, unstable nature made it a real hazard. Mules were taken over one at a time; not till one was safely off was another allowed on. Sometimes the artillery pack mules were unloaded and the cannoneers manhandled howitzer components. When night came, crossing stopped. Meanwhile, the rains fell. Bad visibility precluded airdropping, so it was a wet, cold, and hungry unit that finally stumbled into bivouac across the Shweli. Because of the rain and the search for a crossing site, it was not until 10 January that the 124th was over the river and ready to march for Mong Wi.12 Heavey was not to have the privilege of taking the 124th into combat. The strain of the march was too much; he was relieved and evacuated from a liaison plane strip cut out near the Shweli.13

Concentration of MARS Task Force was screened by two patrol bases of battalion strength, established by the 475th on 6 January. Behind them the 475th waited for a supply drop at Mong Wi, as the 124th pressed eastward. The 475th's wait was a wet and hungry one, then the weather cleared and the transports brought food. Their stomachs full at last, the combat infantry troops were ready to move, and received their orders 8 January. From the soldiers' point of view the ground between Mong Wi and the Burma Road was no improvement over that between Tonkwa and Mong Wi. The central portion of the Loi Lum Range that separates Mong Wi and the Burma Road is between 5,000 and 7,000 feet high, with trails so difficult that some of the mules could not hold to them, and fell over the side. Some stretches were so steep that men could climb only for a minute or two, then had to rest.

General Willey began to deploy his two regiments over 10 and 11 January. Easterbrook was made responsible for the opening of operations against the road. Willey told him that with help from the 124th he was to disrupt traffic on the Burma Road and to prepare a detailed plan of operations and submit it for approval. The 124th would occupy the Mong Wi area and free the 475th to advance. Then Willey reflected, and decided that more than the 475th would be needed along the Burma Road, for on 13 January both regiments were alerted for operations against the road. Willey also tried, but unsuccessfully, to obtain the services of the Chinese 1st Separate Regiment. NCAC refused, but Willey's request made clear that he wanted to drive on the Burma Road with the equivalent of a U.S. division.14

While the 475th had been moving forward, the 124th had been resting and resupplying at Mong Wi. The break ended 15 January, and it set out for the Burma Road in the wake of the 475th. Again the march was a hungry one. The 124th's destination was Kawngsong, to the north and somewhat forward of the points the 475th was to seize. This meant that the 124th had to swing around the 475th and up ahead of it. To do this in rain, night, and woods was not easy; as the men moved into line two squadrons lost their way and bumped into the rear elements of the 475th. The tangle was straightened out, and as the scouts of the 475th were eying a quiet group of bamboo huts, the 124th was moving around the 475th's left flank.15

Harassing Japanese Traffic

Since General Willey understood that the MARS role was to encourage the Chinese to greater celerity in doing their part to secure the land route to China and had been ordered to hold down casualties, he did not try to place the 475th squarely astride the Burma Road, but gave it a mission that was qualified and hedged. He directed Easterbrook to strike against the Wanting-Hsenwi section of the Burma Road, to disrupt supply arrangements, and to place a roadblock, but not to become so deeply involved that he could not extricate his force. Willey also warned him to consider that he might be attacked from almost any side.16

The Japanese, for their part, had the 56th Division plus the 168th Regiment of the 49th Division well north of the Hosi area, and the 4th Regiment (Ichikari), 2d Division, and the Yamazaki Detachment (about a regiment) just south and northwest of Namhpakka respectively. Namhpakka was a sensitive point, for it held a big Japanese ammunition dump. The 4th Regiment, of about 1,000 men, was the unit that MARS now faced. But the other Japanese to the north and west were expected by MARS to react strongly, though for obvious reasons their strength, which was 11,500, was unknown. Since their mission was to help in the decisive struggle now taking form around Mandalay, the Japanese had no alternative but to make their way past MARS as best geography and the fortunes of battle permitted.17

The ground over which MARS and the Japanese clashed changed in character east of a north-south line about two miles east of Ho-pong. (Map 11) West of that imaginary line, the streams, flowing west, carved the earth so that the ridge lines ran east and west; MARS had gone east along the ridge

Map 11

The MARS Force

19 January 1945

lines. Now, east of Ho-pong, the Americans found that the drainage pattern and the terrain had changed, for here the ridges, streams, and valleys ran generally north and south. One reason was a fair-sized stream about five miles to the south whose tributaries were cutting the ground along north-south lines.

About two and one half miles east of the ridge on which squats Ho-pong village, the next ridge line, reflecting the changed topography, bends to the south and east in an arc. On one of its peaks is a village of the Palaung tribe, Nawhkam, consisting of some forty bamboo huts or bashas on either side of the ridge-top trail. One mile east of Nawhkam is a little alluvial valley, perhaps three miles long and a half mile wide. One can imagine that the Palaungs tilled their rice fields there in better days, and perched their village on the ridge line for coolness and defense. Along the eastern edge of this narrow valley a string of three hills rises from 250 to 900 feet above the valley floor which is 3,600 feet above sea level. The southernmost and the highest of the three (in reality the northern end of a larger ridge) became known to the Americans as the Loi-kang ridge, after the Kachin village on its crest. The bean-shaped 3,850-foot hill in the center is the lowest, while the sprawling mass of the third hill near the northern end of the valley is approximately 4,250 feet high. From one to one and a half miles to the east of the hills is the Burma Road, the ultimate objective of the MARS Task Force. On the road, and behind the 4,250-foot hill, is Namhpakka. The size of the area can be estimated from Nawhkam's being three miles from the Burma Road. The action would be fought in an arena about four miles by four miles.

The terrain features are covered with woods and undergrowth. Visibility along the ground is often restricted and fields of fire are not too good. The Burma Road, however, is clearly visible from the dominant features.

The immediate objective of the 475th, the first step toward the Burma Road, was the high ground (estimated at the time to be 4,750 feet in altitude) in the area of Nawhkam village. The trail from Ho-pong led east, down a ravine, up the steep hillside, then onto the ridge where Nawhkam stood. Once this ridge was taken, the little alluvial valley that offered a protected site for supply installations would be dominated; the next step would be to cross the valley and get on top of Loi-kang ridge.

To hold off possible Japanese reinforcements, Company I of the 3d Battalion and two companies of Kachin Rangers were sent five miles north with orders to block the road from the Shweli valley to Namhpakka on the Burma Road.

The 1st Battalion moved out 17 January, behind the Intelligence and Reconnaissance Platoon, and ahead of both, in that loneliest of positions, lead scout, were two veterans of the GALAHAD Force, S. Sgts. Ernest Reid

MARSMEN CUT CROSS-COUNTRY over mountainous terrain to reach their objective, 15 January 1945.

and Chester C. Wilson. The march went on, a quick tumble down the slope to the ravine, then the slow climb up, and the advance south and east on the ridge top. The hours went by, to about 1000. Approaching Nawhkam, the scouts moved off to the north flank, then cut south into the scraggly line of bashas. Down the trail which formed the main--and only--street they went. At the south end a Japanese soldier at the door of a basha saw them, and fired at Sergeant Reid. Reid's luck held, for the shot missed. Japanese scrambled out of the bashas at the end of the village, ran south, and the fight was on. The Japanese, later estimated at two squads, quickly took position on a knoll seventy-five yards south. The Intelligence and Reconnaissance Platoon deployed and under cover of its fire Reid and Wilson pulled back into safety. The battalion commander, Lt. Col. Caifson Johnson, a former Big Ten wrestling champion and football player from Minnesota, committed Company B, and in eighty minutes the now smoking village was free of the Japanese outposts, at a cost of one American wounded.

Clearing the ridge continued in the afternoon. Another Japanese outpost was discovered at the southern end of the ridge, contained, and disposed of on 18 January. While the action was under way, an airdrop, most welcome to the hungry troops, was received at 1430.

Late in the afternoon, the move toward the Burma Road began to yield its first dividends. The 612th Field Artillery, beginning its occupation of positions around 1630, immediately registered on the Burma Road, range about 4,000 yards, with good observation. Japanese daylight traffic along the Burma Road to the 56th Division could now be interdicted.

At this point the 1st Battalion had secured the ridge top, and the 2d Battalion was in position about two miles southwest of the south end of the ridge line, separated from the 1st Battalion by another ridge on which was the Japanese-occupied village of Ho-naw. Until the Japanese were driven from Ho-Naw, the 1st Battalion was to hold on the ridge. The 3d Battalion was in the process of moving northeast through the 1st Battalion's position, on its way to assembly areas from which to seize ground directly overlooking the Burma Road.18 So far the operation had gone like clockwork against the lightest of opposition from outposts.

The morning of 18 January efforts began to take positions dominating the Burma Road. The objectives of the attack were the three hills along the eastern edge of the little alluvial valley. The plan called for the 2d Battalion, 475th, to establish a position on the north end of Loi-kang ridge, the 3d Battalion to take the 3,850-foot hill, and the 3d Squadron, the hill which overlooks Namhpakka.

The 3d Battalion took its objective with ease, moving up the hillside

against minor opposition, estimated at perhaps two squads. For the Japanese as yet had not reacted to the MARS advance by bringing troops from elsewhere. The 2d Battalion, which had to use a circuitous route from its positions to the south, did not attack until afternoon. Crossing the valley, it climbed up the north end of Loi-kang ridge, and began moving south. Around 1600 it met the first real opposition, as "all hell broke loose" from Japanese fire strong enough to stop the battalion's advance. The fire came from elements of the local garrison, the 1st and 2d Battalions, 4th Regiment, 2d Division.19

The 3d Squadron in advancing to its jump-off position moved behind the 2d Battalion until such time as the latter turned east to its objective; then the cavalrymen continued on north and east toward theirs. This procedure was time consuming; the 124th would not be in place to attack until 19 January. The troops had but the lightest contact with the Japanese on the 18th, resulting in one trooper slightly wounded.20

Meanwhile the 2d Battalion found itself in a fight. The Japanese had fortified the ridge north of Loi-Kang village, and held stubbornly along the crest. The battalion had a hard time establishing itself on the ridge, what with darkness falling and wounded having to be brought down. Japanese counterattacks briefly cut off a platoon, but by evening the 2d Battalion had a perimeter on the side of the hill and was firmly in place, though the crest and the southern end, on which was Loi-kang village, still were in Japanese hands. The 1st Battalion took its objective, Ho-naw village, with two men wounded. Johnson's men found twenty-four Japanese packs, suggesting a hasty flight.21

The 612th Field Artillery took advantage of its commanding position and excellent observation to attack what the 475th's commander recorded as "beautiful targets." The Tenth Air Force, which, co-ordinated by an air support liaison group, was to be much in evidence in the days ahead, bombed Namhpakka. The transports came in for airdrops in the valley, and the drop field began operation under hazards that were to last for the rest of the action, for the Japanese on their end of Loi-kang ridge had perfect observation down the little valley. They promptly called for artillery and mortar fire. The Japanese had two 150-mm. howitzers in the area; their presence was soon felt.22

MARSMEN ON LOI-KANG RIDGE. The Japanese were driven from the crest of the ridge by the 2d Battalion, 475th Infantry, 19 January 1945.While these operations were under way, Willey sought to bring up reinforcements of men and artillery. On 18 January he tried to persuade NCAC to use the Chinese 1st Separate Infantry Regiment. Sultan disapproved the request. Attempts to obtain the presence of Chinese 105- and 155-mm. artillery, to counter the effective Japanese 150-mm. howitzers, also failed. After the war Willey was at a loss to know why the Chinese 1st Separate Infantry Regiment, originally intended to operate as part of a division, was kept in NCAC reserve. He surmised that the Chinese objected to its being under American command, and that for essentially diplomatic reasons General Sultan had yielded.23

General Willey also recalled later that another command problem concerned and hindered him. He believed that his airdrop field had to be

JAPANESE TRUCK AND TANKETTE trapped by crater blown in the Burma Road by MARS demolition men.covered at all costs, and so he could not maneuver as freely as he would have liked. A quarterback whose team had the ball within its 10-yard line would sympathize with the military problem; both Willey and the quarterback would be limited in their choice of maneuvers even though both were on the attack.24

That night, the 18th, the Japanese received reinforcements for their position in the Namhpakka area. The Yamazaki Detachment, under orders from 33d Army, was moved back from the vicinity of Namhkam to link the 4th Regiment with the main concentration to the north.25

On 19 January, MARS Task Force made an attempt to block the Burma Road by demolition. From the 3d Battalion, a patrol was sent out under T. Sgt. Alfred T. Martin. Sergeant Martin had the distinction of being the

first American to set foot on the Burma Road in this area. He and his patrol successfully blew a crater in the road, then withdrew. The 612th Field Artillery, meanwhile, fired on a number of profitable Japanese targets, and believed they succeeded in knocking out four Japanese tankettes. Two were caught on the road, and two more to the north of the 3d Battalion.

This same day the 2d Battalion reached the crest of Loi-kang ridge. When the battalion had organized its position, the executive, Maj. John H. Lattin, noted in his diary that the first attack at 0900 had "bogged down" with Japanese dug in on both the sides and crest of the ridge. Around 1300 hours the decision was made to charge straight ahead for there was no room to maneuver. At 1400 Thrailkill's men went right on up the ridge and had the satisfaction of seeing the Japanese run. The Americans lost seven killed and seventeen wounded but had driven the Japanese from the crest of a very defensible position.26

To the north, the 3d Squadron of the cavalry moved on to its hill top objective, also on 19 January, in late afternoon under Japanese mortar and artillery fire. Two brushes with Japanese patrols, one of which was hit by an artillery concentration for twelve counted dead, gave the 124th its first contact with the Japanese soldier. That night the troopers dug in where they were to wait for morning and a chance to organize a systematic defense.27

The 124th's artillery support was being given by the 613th Field Artillery, which brought its twelve 75-mm. pack howitzers into action on 19 January. The 613th's commander, Colonel Donovan, was able to fight his battalion as a unit, with batteries under the control of fire direction center, and battalion concentrations ready on call. After the war Donovan stated that, in contrast, the batteries of the 612th Field Artillery were usually detached to the control of the 475th's battalion commanders. Using aerial observation, the 613th put a Japanese 150-mm. howitzer out of action at the extreme range of its little howitzers.28

To these activities the Japanese began to react more strongly than they had earlier. Two attacks at daybreak on the 3d Battalion suggest that the Yamazaki Detachment was making its presence felt.29

Sergeant Martin's blowing a crater in the Burma Road, the artillery's placing fire on what had been the artery of supply and evacuation of the 56th Division, and the fact that three battalions were less than 2,000 yards from the road suggested to the local commanders that the time had come to move

across the Burma Road and clamp it shut. The first phase, that of getting established along the road, was over.

The Block Disapproved

For a day or two heavy action seemed imminent as troops of the 2d Battalion tried to move south on 19 January from their part of Loi-kang ridge and consolidate their positions. Between the 2d Battalion and Loi-kang village was a group of Japanese, well dug in, and with plenty of machine guns and 82-mm. mortars. The local terrain favored the defense, for the ridge at this point was a razorback. Trying to advance off the trail, which ran along the crest directly into the Japanese machine guns, the men of the 2d Battalion found themselves on slopes so steep they had to cling to the brush with their hands or creep on all fours. Frontal assault seemed the only solution, and the 3d Platoon, Company F, T. Sgt. Patrick W. Murphy, delivered one that took the Japanese positions to the direct front. At the day's end, the battalion had a better position but the Japanese at their end of the ridge were still able to place observed fire on American supply and command installations in the little valley. Something would have to be done about the Japanese end of Loi-kang ridge.30

Dawn of 20 January revealed to the 3d Squadron troopers that their first positions were on the reverse crest of their objective. Being on the reverse, they lacked the observation and fields of fire over the Burma Road that were their aim. There were Japanese to the direct front and it was necessary to attack. The hill was carried against opposition that yielded fifty counted Japanese dead; then, as the squadron was reorganizing, the Japanese struck back twice supported by strong artillery fire. The squadron at 1100 withdrew slightly to obtain a smaller perimeter. Fortunately, by noon the 1st Squadron was within supporting distance. Troops A and B were attached to the 3d Squadron while Troop C and headquarters went on to their objective, a hill about two miles northwest of Namhpakka. The 3d Squadron attacked again on the morning of the 21st. By afternoon it could report the situation secure and ask for a mail drop. The squadron had lost only four killed, seven wounded. This success of the 124th meant that by morning of the 21st four battalions were lined up along the Burma Road. Of the four, only the 2d had encountered stiff resistance, but some at least of the problems it faced could be ascribed to the difficulty of bringing heavy pressure to bear under the peculiar terrain conditions.31

Japanese resistance to date was not imposing, and Colonel Easterbrook

decided to request permission to take further offensive action. Although Japanese counterattacks, like those on the 20th against the 124th, and two more launched against the 3d Battalion had been repulsed, Japanese artillery fire at night was a distinct hazard, and was causing heavy casualties among the mules.

On 21 January Easterbrook asked General Willey for permission to move the 3d Battalion to a ridge just east of the Burma Road, "if and when we get some supplies." In justification for the move it could be argued that while MARS was harassing Japanese traffic along the Burma Road it was not stopping it. Thus, the 2d Battalion that same day had planted mines and booby traps along the road. The next night two Japanese trucks blew up on the road, but the night after that Japanese armor was using the road at a cost of only one tankette disabled by a mine. As for the 124th, its unofficial unit historian noted that "nearly every night" Japanese trucks could be heard going by. Plainly, the mines and ambushes of the MARS Task Force were not cutting off traffic on the Burma Road, to say nothing of the bypass trails to the east. Moreover, on 21 January, leading elements of the Chinese 114th Regiment contacted U.S. patrols as they entered the area to the north, so the Allied position was growing stronger. On 22 January patrols actually reached the ridge on the far side of the road; the battalion might have been able to follow.32

But on that same day of 22 January, word came back from 5332d Brigade headquarters at Myitkyina that the plan to move east was disapproved "at this time." "Plan is good," radioed Willey, "but I have no report on Allied activities to the north." After the war, Willey recalled having considered that the success of the proposed operation depended upon its co-ordination with the Chinese and upon the supply situation. Willey's radio shows that he was concerned about co-ordination. So, for the present, MARS Task Force would confine itself to patrols, demolitions, and artillery fire.33

Patrols and ambushes offered ample scope for courage and enterprise among small unit commanders. Between 21 and 28 January the patrols made their sweeps and laid their ambushes with varying results. Ration deliveries were irregular because Japanese fire interfered with the transports as they came over for their supply drops. From 14 to 26 January the 2d Battalion, 475th, was on reduced rations, though ammunition came in steadily.34

During this week of patrolling by day and Japanese raids and artillery fire by night, several incidents of note occurred. The 124th Cavalry located a

MORTAR SQUAD, 124TH CAVALRY, cleans and oils an 81-mm. M1 mortar during a lull in operations, 22 January 1945.Japanese ammunition dump near the 3d Battalion's positions. The 3d sent out a patrol and blew up the stockpile, with 3,000 rounds of 70-, 75-, and 105-mm., 400 rounds of grenade discharger, and 12 cans of small arms ammunition, and 18 drums of gasoline. Two tankettes were destroyed the night of 23-24 January. The Japanese tallied on the 25th by ambushing a 2d Battalion patrol, killing three Americans and wounding four.35

Meanwhile, this pressure by MARS Task Force and that of the Chinese forces in the north began to register on the Japanese. The soldiers of the 4th Regiment, 2d Division, could see the aerial activity that kept MARS supplied. Not recognizing what they saw, they were so impressed by a big supply drop on the 24th that they sent a report to the 56th Division of a large

airborne force being landed along the Burma Road. Accepting this report, the 56th's commander passed it on to the 33d Army and Burma Area Army. He added that he proposed to destroy his ammunition and retreat south. His superiors on 24 January agreed to let him retreat, but only after he had evacuated casualties and ammunition. Forty vehicles with gasoline accompanied by a Major Kibino of the 33d Army staff were sent north to support the 56th in its withdrawal.36

The Japanese truck convoy made its run north the night of 24 January. The trucks were heard, and the Americans placed heavy fire on the road. Kibino had been making the trip in a tankette. Hit by a 4.2-inch mortar shell, it burst into flames clearly visible from the American lines. Kibino clambered out, jumped on a truck, and succeeded in getting his convoy through to the 56th Division. Next day the derelict tankette was credited to the 2d Battalion, 475th Infantry.37

With fuel and additional trucks at their disposal the Japanese began the difficult and dangerous task of running past the MARS positions. The Japanese of necessity had to move by night, and they seem to have adopted, for this reason, the tactic of keeping the Americans under pressure by heavy shelling during the night, by counterbattery with 150-mm. artillery, and by night raids. These diversionary operations were personally directed by the 33d Army chief of staff.38

Meanwhile, the Chinese 114th Regiment, which had arrived in the general area 21 January, was slowly moving toward the road, north of MARS's lines and much closer to the 56th Division. The commander Col. Peng Ko-li had conferred with Colonels Osborne and Easterbrook and, after the meeting, gave the impression that their plans had not been clearly defined to him.39 Peng's comments to higher Chinese authority may have been fairly vigorous, for the commander of the New First Army, General Sun Li-jen, through his American liaison officer, told Headquarters, NCAC, that MARS Task Force had not cut the Burma Road near Hosi. Instead it had five battalions lined up on the hills and the Americans had refused to let the 114th Regiment through their lines to attack Namhpakka, so that the 3d Battalion, 114th Regiment, had turned northeast and cut the Burma Road at the eighty-mile road mark from Lashio on 22 January.40

According to the American records, based on liaison officer reports, the Chinese occupied two blocking positions on 27 January, suggesting that they

had used the interim in moving up. The 3d Battalion took high ground just east of Milestone 82, five miles north of MARS's lines, while the 1st Battalion put a company less a platoon on the east side of the road at Milestone 81. A Chinese battery took position about two miles west, in the hills.

Between the 23d and the 27th, the latter being the date the road to China was opened, the Japanese had evacuated "more than a thousand casualties and several hundred tons of ammunition." Their account lacks detail, but references to the situation's becoming critical around 30 January probably tell what followed when the Chinese actually crossed the road.

The 3d Battalion was shelled and attacked for five days running, until the men were falling asleep in their foxholes. As for the lone Chinese company blocking the Burma Road, the Japanese reconnoitered its position the night of 28 January and also checked the defenses of the Chinese battery supporting the 114th. Next night the Japanese attacked. The battery position was overrun and three howitzers neutralized by demolition charges. The solitary Chinese company trying to stand between the 56th Division and safety was almost destroyed. As these disasters were being suffered the Japanese were continuing their blows at the 3d Battalion, Chinese 114th Regiment, which stoutly held its hilltop positions.

The successes of the Japanese on the night of 29 January were sufficient for their purpose. Colonel Peng had advanced a minor piece on the game board and lost it. He accepted the situation and did not again try to stop the 56th Division's retreat by a roadblock. The events of 27-29 January, when the Japanese succeeded in getting past the Chinese while the American forces were not astride the Burma Road or supporting the Chinese, brought some later recrimination. The vice-commander of the 38th Division, Dr. Ho, writing after the war, echoed General Sun's complaint that MARS had failed to cut the Burma Road, thus permitting the Japanese to concentrate on his men.41

In their battalion perimeter defenses along the west side of the Burma Road, the Americans during this period received some of the impact of the Japanese effort, mostly persistent shelling, the greater weight of which may have fallen on the 2d Battalion, 475th. The Japanese did not neglect counterbattery, and by 29 January the 612th Field Artillery had three of its 75-mm. howitzers silenced by 150-mm. shells. On the 26th four men of the 2d Battalion were almost buried alive by a Japanese shell, while two U.S. machine guns were destroyed. Casualty figures for the 475th show that by 29 January there had been 32 men killed and 199 wounded. The 612th Field Artillery had twice as many casualties as did the 1st Battalion, which was then in reserve, and the 2d Battalion had as many as the other two battalions

and the artillery combined. For their part, the men of MARS Task Force continued with daylight patrolling, booby-trapping, mining, and shelling the road, plus some minor offensive action.42

An attempt by Company L, 3d Battalion, to clear the Japanese from Hill 77, just west of Milestone 77 on the Burma Road, whence its name, was a failure. After a heavy mortar barrage on 28 January, Company L went forward. The Japanese were unshaken, and swept the company headquarters with machine gun fire. The company commander and forward platoon leader with four enlisted men were killed. 1st Lt. Aaron E. Hawes, Jr., took command and brought the company back to the battalion perimeter.43

To the north of the valley, the 124th Cavalry had found that Japanese fire from a small hill just a few hundred yards from its lines was a serious hazard. The final decision was to drive off the Japanese with Troop A, reinforced by a platoon of C, on 29 January. Troop B and the 613th Field Artillery would give supporting fire. Since the attack was mounted in broad daylight, witnessed by many men from their hillside vantage spots, and executed with speed and precision, witnesses were inevitably reminded of a service school demonstration to show the advantages of fire and movement in the attack.

The Japanese held a ring of little bunkers around the crest of the hill. Each attacking platoon had a rocket launcher team attached to smash firing slits and blind the defenders. Moving as fast as the rough terrain permitted, the troopers used a small draw for their avenue of approach, then spread out for the climb up the hill. They fired as they moved. When the range permitted, grenades were hurled into the Japanese bunkers and dugouts. The combination of speed, fire, and movement worked well, and in two hours the fight was over, at a cost of eleven wounded. Thirty-four dead Japanese were found.44

The Japanese retaliated with heavy artillery fire all day and on into the night. As the darkness fell, there was apprehension that the Japanese would attack in strength that night. They did, twice, and in one desperate rush broke into Troop B's perimeter, overrunning a platoon command post. There was a brief, murderous clash in the darkness, and then the Japanese were gone, leaving four dead. Elsewhere, sounds in the darkness indicated that other Japanese were looking for the airdrop field. Later discoveries of U.S. rations in enemy positions suggest that the Japanese succeeded in getting some supplies.45

AN 81-MM. MORTAR CREW shelling the Burma Road.In these minor episodes gradually disappeared any thought that MARS's presence on the battlefield might lead the Chinese to greater speed of movement. The principal impact on Sino-American relations in the local scene seems to have been the misunderstanding as to whether MARS was to place itself squarely across the Burma Road. Elsewhere in Burma the failure of the Chinese and American forces under NCAC to hold the 56th Division in north Burma severely limited their contribution to SEAC's operations farther south, while their inability to destroy the 56th meant that not until the Japanese withdrawal from north Burma made further progress could MARS and the Chinese be released for service in China.

Table of Contents ** Previous Chapter (5) * Next Chapter (7)

Footnotes

3. (1) NCAC History, II, 237. (2) Willey comments on draft MS.

4. (1) NCAC History, II, pp. 237-38. (2) Willey comments on draft MS.

5. History of the 5332d, Chs. VI, IV.

6. Ibid.

7. Randolph, Marsmen in Burma, pp. 17, 56.

8. Ibid., pp. 73-92.

10. (1) FO 22, Hq NCAC, 26 Dec 44. (2) Willey comments on draft MS.

11. Rad, TOO 0640, 31 Dec 44. 475th Radio File, NCAC Files, KCRC.

12. (1) Daily Jnl, 124th Cavalry. NCAC Files, KCRC. (2) Diary of Lt Col John H. Lattin, Exec Officer, 2d Bn, 475th Inf. OCMH. (Hereafter, Lattin Diary.) (3) Randolph, Marsmen in Burma, pp. 108-27.

13. Randolph, Marsmen in Burma, p. 125.

14. Rad, NCAC to 5332d, 0617 10 Jan 45; Rad, Willey to Easterbrook, 7 Jan 45; Rad, Willey to Heavey, 10 Jan 45; Warning Order, 13 Jan 45; Rad, Willey to NCAC, 11 Jan 45. 5332d G-3 Jnl, KCRC.

15. (1) NCAC History, III, 302. (2) Daily Jnl, 2/475th Bn. KCRC.

16. (1) Rad, Willey to Easterbrook, 10 Jan 45. 5332d G-3 Jnl. (2) Willey comments on draft MS: "Orders to me from the start not to lose U.S. men unnecessarily." (3) The Chinese did not know of these restrictions on MARS Force and expected it to block the road. Dupuy Comments.

17. Japanese Study 148.

18. Ltr, Easterbrook to Col J. W. Stilwell, Jr., 28 Jan 45; Easterbrook Notebook, 17 Jan 45. Easterbrook Papers.

19. (1) Easterbrook Notebook, 18 Jan 45. (2) Daily Jnl, 2/475th Bn. (3) Japanese Study 148, p. 46. (4) Statement, Superior Private Yoshio Sato. Folder 62J, 441-450, NCAC Files, KCRC. Sato claimed that the 3d Battalion was in Java. (5) Johnson comments on draft MS. (6) Quote from Lattin Diary.

20. Daily Jnl, 124th Cav.

21. (1) NCAC History, III, 301. (2) Easterbrook Situation Map. (3) Quote from Easterbrook Notebook, 19 Jan 45. (4) Johnson comments on draft MS. (5) Lattin Diary.

22. (1) Easterbrook Notebook, 18 Jan 45. (2) Willey comments on draft MS.

23. (1) Willey comments on draft MS. (2) Rad, Willey to NCAC, 18 Jan 45; Rad, NCAC to Willey, 19 Jan 45. 5332d G-3 Jnl.

24. Willey comments on draft MS.

25. Japanese Study 148, p. 46.

26. Lattin Diary, 19 Jan 45.

27. (1) Daily Jnl, 124th Cav. (2) Randolph, Marsmen in Burma, pp. 149-50.

28. (1) Ltr, Col Donovan to Gen Smith, 6 Nov 53. OCMH. (2) Willey comments on the draft manuscript of this volume also mentions the successful counterbattery by the 613th.

29. (1) NCAC History, III, 302. (2) Easterbrook Notebook, 19 Jan 45. (3) Daily Jnl, 124th Cav.

30. (1) Easterbrook Notebook, 20 Jan 45. (2) Randolph, Marsmen in Burma, pp. 148-49.

31. (1) Daily Jnl, 124th Cav. (2) Randolph, Marsmen in Burma.

32. (1) Easterbrook Notebook. (2) Randolph, Marsmen in Burma, p. 158. (3) Opns Jnl, 2/475th Inf, 21-23 Jan 45. (4) The proposal is Item 12, 21 Jan 45, 5332d G-3 Jnl.

33. (1) Easterbrook Notebook. (2) Quotation is from Rad, Willey to Easterbrook, 21 Jan 45. 5332d G-3 Jnl. (3) Willey comments on draft MS.

34. Lattin Diary.

35. (1) Easterbrook Notebook. (2) Daily Jnls, 124th Cav, 475th Inf.

36. Japanese Study 148, pp. 47-48.

37. (1) Ibid., p. 48. (2) Easterbrook Notebook, 24 January 1945, speaks of the "fireworks" on the road.

38. (1) Japanese Study 148, p. 49. (2) Easterbrook Notebook, 29 January 1945, mentions 150-mm. counterbattery. (3) Lattin Diary.

39. NCAC History, III, 277.

40. Rad 310, 22 Jan 45. 38th Div Rad File, NCAC Files, KCRC.

41. (1) NCAC History, III, 277-79. (2) Ho Yung-chi, The Big Circle, p. 139. (3) Japanese Study 148. (4) Dupuy Comments.

42. (1) Daily Jnl, 2/475th Inf. (2) Easterbrook Notebook, 26-29 Jan 45.

43. (1) Easterbrook Notebook, 28 Jan 45. (2) Hawes won the Silver Star. GO 81, par. V, Hq USF IBT, 26 Apr 45.

44. (1) Randolph, Marsmen in Burma, p. 168, describes the fight. (2) Rpt, 1st Lt Arthur A. Rubli, Adj 3d Squadron, to CO 124th Cav, 12 Feb 45, sub: Casualties. Daily Jnl, 124th Cav.

45. Randolph, Marsmen in Burma, pp. 169-70.